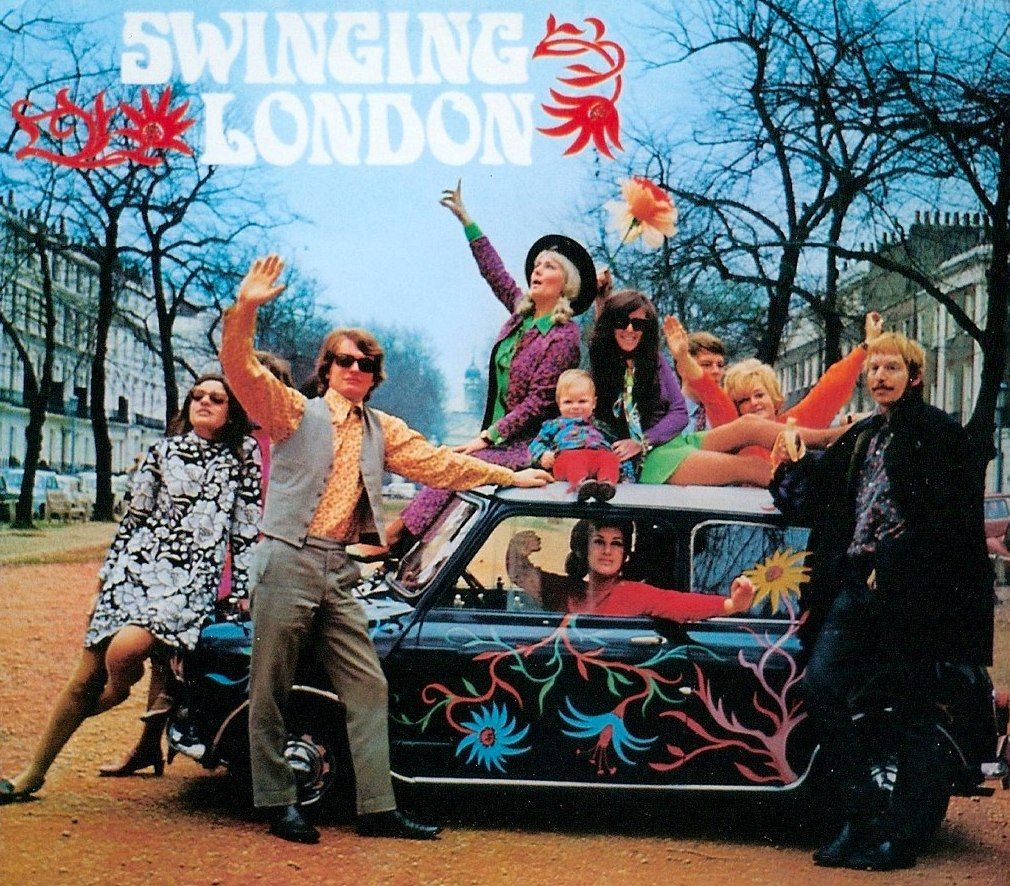

Today's blog post is about Swinging London; a moment in time that reconfigured the music, fashion, movies and books of the youth culture.

“There came a moment when London first shook off the coils of hidebound British society, the sobriety of convention, the obedience of norms that had made it a boring place in its post-war years. As no other city has ever done, London suddenly owned a whole decade and became synonymous with the culture of that decade—the 1960's. There was a cultural and social insurrection that transformed every idea of what was permissible in society and in the arts.” (Daily Beast)

Ready, Steady, Go!: The Smashing Rise and Giddy Fall of Swinging London

In the opening of his in his brilliant book, Ready, Steady Go! (Doubleday 2002), Shawn Levy captures how Swinging London came about:

“Britain in the mid-1950s was everything it had been for decades, even centuries: world power; sire of glorious intellectual, aesthetic and political traditions; gritty vanquisher of the Nazis; civilizing docent to whippersnapper America; bastion of decency, decorum and the done thing. But somehow, in sum, it was less. The States, France, Italy all felt modern. Rock music and the rise of the teenager as tastemaker made the American scene come on, naturally, loudest, while decadent, savvy, grown-up style made existential Paris and La Dolce Vita Rome meccas for both the international jet set and an emerging global bohemian underground. England, by contrast, was dowdy, rigid and, above all, unrelentingly gray, gray to its core.

By 1956, the British economy had finally relaunched itself: Key industries were denationalized by a Conservative government; American multinationals were choosing Britain as the home base for their expansion into Europe; unemployment dipped, spiking the housing, automobile and durable goods markets; credit restrictions were eased, encouraging a boom in consumerism; the value of property—particularly bombed-out inner-city sites—soared. In just three years, the English stock market more than doubled in value, and the pound rose sharply in currency markets. Inevitably, as in America, prosperity led to complacency and nostalgia for a prewar era that only in retrospect seemed golden. There was no widely held notion of “cool” or “hip.” The mood, taken at large, was smug—or would have been, if smugness were considered good form.

The common conception of big city excitement—women in long skirts, men in dinner jackets, dance band music, French cuisine, a Noël Coward play and a chauffeured Rolls—was just as it might have been in the twenties…’There was nothing for young people,’ remembered fashion designer Mary Quant, ‘and no place to go and no sort of excitement.’ But as, again, in America, there were intimations of a burgeoning dissatisfaction with the status quo that had become the landscape. And, perhaps because it had been beaten down for so long, or perhaps because its increasing marginalization on the world stage liberated it from grave responsibilities, Britain seemed particularly fertile ground for this sort of seed.

London rose from a prim and fusty capital to the fashionable center of the modern world and then retreated. The fifties were Paris and Rome. The seventies, California, Miami and New York. But the sixties, that was Swinging London—the place where our modern world began. Hardly any of the elements were unique: There had been bohemian revolutions and economic renaissances and new waves in the arts and popular culture and lifestyle before. There had even been other moments when youth dominated the scene: The Jazz Age of the twenties, the brief rock ’n’ roll heyday of the fifties. But in London for those few evanescent years it all came together: youth, pop music, fashion, celebrity, satire, crime, fine art, sexuality, scandal, theater, cinema, drugs, media: the whole mad modern stew.

It wasn’t youth culture that England invented: From James Dean to Levi’s to Elvis, that was America through and through. But where American official culture at the end of the fifties had effectively tamped down the expressive impulses of young people, England embraced them as a way of emerging from decades—maybe centuries—of slumber. It let them grow, coalesce, strut. London was where youth culture finally cemented its hold on all forms of expression, and made itself loudly and exuberantly known. Youth, once something to endure, transformed in the span of a few years of British sensations into a valuable form of currency, the font of taste and fashion, the only age, seemingly, that mattered. The Brits who created Swinging London were unique in their resilience, their ability to absorb and transform elements of American and Continental culture and the cocksureness with which they flaunted their invention of themselves.

By the early sixties, the city positively overflowed with out-of-nowhere high energy. At night in London, anything could happen: You might attend a concert by a band of geniuses who would create music worth remembering for decades or see a fortune come and go gambling at an elegant casino in Mayfair or learn the Twist at a trendy discotheque near Piccadilly or smoke pot at an after-hours Caribbean joint in Notting Hill or laugh out loud at the old fart prime minister being lampooned on a West End stage or at a nightclub in Soho. And those were just the outward signs: If you looked harder you could find a bold, spirited and, crucially, employed generation of young people with education, access to birth control, freedom from mandatory military service, a new culture of morals and sensations being reinvented daily and no particular sense that the old ways were set in stone. These were English people who’d absorbed the sensibilities and attitudes of the French and the Italians and grafted them onto the materialism and energy of the Americans. They’d invented themselves as living works of art in a way no Britons had since Oscar Wilde… London had suddenly become the hottest place in the world: New York and Paris and Los Angeles and Rome combined. Nowhere previously had such an agglomeration of globally noted talents combined at one time and with one such sense of common tenor—not to mention the inestimable advantage of tender age. For a few years, the most amazing thing in the world to be was British, creative and young.

And for all the sweep of history and all the pop artifacts and all the indescribable meteorology of human taste, attitude and passion, Swinging London was built of individuals. People became icons because they did something first and uniquely. Everybody overlapped and partied together and slept and turned on and played at being geniuses together, but a few stood out and even symbolized the times: eminent Swinging Londoners, wearing their era like skin. It would be possible, in fact, to explain the age by telling their stories.

The Snapper, David Bailey, was one of the first on the scene, an East End stirrer and mixer and the most famous of the new breed of fashion photographers who helped revolutionize the glossy magazines and popularize the new hairstyles, clothing and demeanor.

The Crimper, Vidal Sassoon, also from an East End background, but Jewish and, amazingly, a real warrior, who freed women from sitting under hairdryers and ascended into an unimaginable ether: flying to Hollywood to cut starlets’ hair and branding himself into an international trademark.

The Draper, Mary Quant, took a Peter Pan–ish impulse to not grow up and sicced her craft, inspiration and diligence on it, creating a new kind of women’s fashion that spoke to the rapidly expanding notions of what it meant to be cool, free and young.

The Dreamer, Terence Stamp, another one from the stereotypical Cockney poverty, who wound up winning acting prizes, with his face on magazines, the most beautiful women in the world on his arm and a home among peers and prime ministers in London’s most prestigious

The Loner, Brian Epstein, who failed miserably at everything until he helped create the greatest entertainment sensation of the century while warring internally against the self-doubts he’d borne his whole life.

The Chameleon, Mick Jagger, a suburban boy with a bourgeois upbringing, who could mimic whatever he wished: black American music, the stage manner of raunchy female performers, the go-go mentality of rising pop bands, the chic manners of slumming aristocrats and the arcane sexual and narcotic practices of bohemians both native and exotic—a quiver of cannily selected arrows that let him survive the decade unscathed while the road behind him was littered with the corpses of friends.

The Blue Blood, Robert Fraser, with every tool that traditional English life could offer a man—birth, schooling, military appointment, connections, polish, bearing—but a restless imagination and a decadent streak that led him into art dealing and sensational living that brought him down.

Lay these lives alongside one another, bang them together, hold them up to the light and you could open an entire time. You could see how people lived and rose and changed and stumbled and faded or kept on rising until they disappeared into the sun. You could see how people made a glory of their day or their days into a glorious apotheosis of themselves. You could hear the music, feel the energy, see the paisley and the op art and the melting, swirling colors. You could go back to Swinging London."

SWINGING LONDON: THE FILMS

"In his book ‘Psychedelic Celluloid: British Pop Music in Film and TV 1965-1974’, Simon Matthews details an era of pop-influenced movies. Film and TV from the mid to late Sixties is not as revered nowadays as the earlier kitchen-sink period, dominated by northern scribes and working-class actors making their names with A Taste Of Honey and This Sporting Life. That Matthews’s opening year makes a useful cut-off between the two eras is illustrated by two Fab Four vehicles. First, 1964’s A Hard Day's Night, a relatively sleek movie, shot in black and white, scripted by Alun Owen, who had earned his stripes on social-realist small-screen dramas, and featuring Steptoe And Son's Wilfrid Brambell.

British pop stars, among them Cliff Richard and Tommy Steele, had appeared in many films, but A Hard Day's Night’s global success was unprecedented. In 1964, it was the ninth highest grossing film in the US – even outselling Elvis Presley's Viva Las Vegas. Matthews argues this was “the single event that brought serious US studio money to London and kickstarted [British pop cinema]”. The film already captured some of the new, more sprightly aesthetic, directed as it was by the American Richard Lester, already a dab hand at comedy thanks to his connections to John Lennon faves The Goons. A Hard Day’s Night also had some of the freewheeling, semi-improvised tone of key continental films, among them La Dolce Vita and Jules et Jim. Lester, though, took this style further a year later in the more exuberant Help!, a surreal comedy chase that came with a far higher budget. The director filmed in colour, set scenes in such exotic locales as the Bahamas and brought on board respected thespians Leo McKern and Eleanor Bron. Its script was co-written by American novelist Marc Behm, previously credited on Cary Grant/Audrey Hepburn thriller Charade. Yet the plot was threadbare, held together with barely relevant, promo-style musical sequences. Still, this became a template for further pop films and a definite influence on The Monkees’ TV show.

In the space of a few months, UK dramas in particular had gone from the dour and threadbare to fashionable and fast-paced, in a way that cast a wide shadow. If any film could incorporate a British group or singer, either acting or in a musical cameo, so much the better. Thus Mick Jagger would lead in Performance, Lennon appeared in How I Won The War and the Arthur Brown Set performed in Roger Vadim’s Jane Fonda-starring The Game Is Over (La curée).

The peak of this wave came around 1970, with pop-influenced movies evolving into more sophisticated forms, with concert films such as Glastonbury Fayre alongside experimental works, notably Tony Garnett’s post-Kes permissive documentary The Body, which featured background music from members of Pink Floyd, much of it devised from human sounds such as heartbeats and sneezes.

The pioneering prog outfit Pink Floyd had already enjoyed a credible cultural impact, beginning with their own light shows, leading to a key scene in the documentary Tonite Let’s All Make Love In London.

By 1971, US studios were beginning to pull the plug on investment in British films in the wake of growing losses. The kudos of UK acts was diminishing, thanks to the break-up of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones’ retreat into tax exile and greater sway for American rock groups and singer/songwriters. British film retreated from youthful positivity and vitality, turning to nostalgia and conservatism. The pop age had ended and looking at these images, we have never gone back." (Psychedelic Celluloid -Simon Matthews)

"The Swinging London of the 60's, that brief magical span between the first squeals of Beatlemania and the dead man’s float of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones—when pop music, photography, fashion, and party-going chemically combined and burst into what Tom Wolfe might call a Happiness Explosion…After the long postwar austerity and damp conformity, Britain was overdue for social release and cultural heave-ho. Watch any documentary about the photographers of that era (David Bailey, Terence Donovan, Duffy) and their favorite models (Jean Shrimpton, Celia Hammond, Paulene Stone), or YouTube the semi-documentary pastiche Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, and behold London sluffing off the prison pinstripes of stiff propriety to go completely mod. Miniskirts, white go-go boots, sherbet-colored slickers, sheepdog bangs, lip frosting, caftans, Chelsea boots, collarless men’s jackets, and Union Jack regalia leapt from the streets to the fashion pages and back again. Just as in New York the advent of Andy Warhol and his Factory superstars was a louche insurgency that would find its orgasmic fulfillment under Studio 54’s coke-spooning moon, London’s overnight aristocracy of the young, beautiful, amateurish, and socially outcast rattled the dentures of the old, established order of birth, rank, and gentility.

No movie captures the exuberant liftoff period better than Richard Lester’s A Hard Day's Night which remains an offhand marvel of daft humor, deft expediency, paper-doll pratfalls, frenzied chases, and hit songs that meshes the deadpan quirks of each Beatle into a vibrating chord. A Hard Day’s Night has a straggling cloud of Chaplin-esque pathos—a sweet reverie on Ringo Starr’s beagle apartness (apt, since he was the last to join the band)—and a phenomenal fillip by Victor Spinetti as a frantic television director that infuse feeling and tension into a film that might otherwise have been a fan magazine in motion. If only Elvis Presley’s vehicles had had such an inventive zeal and chopstick dexterity. (The Beatles-Lester follow-up, Help! suffered from the sophomore strain of sequelitis.) Having a Wild Weekend, starring the Beatles’ then rivals the Dave Clark Five and directed by John Boorman (his feature debut), had a bashy energy, but its sprawling antics resembled an American International Beach Party comedy more than a slice of lemon like A Hard Day’s Night.

Far less known to American audiences than either of these time-capsule trophies is Smashing Time, which Elvis Costello flags as an inspiration in his recent memoir, Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink, saying it stuck in his mind more than many of the serious 60's titles everyone cites. This slapstick satire paired Rita Tushingham and Lynn Redgrave as pals from the North of England who descend upon London, get swept up in the poodle parade of street fashion that is Carnaby Street, become improbable sensations and sneering foes, and somehow manage to trigger a power blackout that leaves the streets deserted, the two of them a trifle woozy but re-united once more and back where they started.

The primary fixation and focus of Swinging London films was the beautiful women of creamy complexion, imperious cheekbones, and Bambi eyelashes pinned like a butterfly in the viewfinder and projected onto the world: screen, billboard, magazine layout, tabloid front page—the male gaze powered through a camera lens and sent forth to multiply. Suzy Kendall! Joanna Lumley! Marianne Faithfull! As the camera obsessed over This Year’s Model or musical moppet, everything around her spun wild and fractured into shattered mirror reflections. Where a traditional studio Hollywood film would frame the female star full-on in lustrous light, like a satin pillow come to life, 60s swingers resorted to eclectic tactics and alienation effects, splicing TV advertising gimmicks, documentary elements (man-on-the-street interviews, spoofs of mellifluous BBC chat programs, protest placards), and French New Wave borrowings (jump cuts, heads juxtaposed against wall posters, cool attitudinizings) into a collage expressing the editorial attack or moral judgment of a super-chic message movie.

Darling—a key Swinging London exhibition, directed by John Schlesinger, who went on to do Midnight Cowboy—opens with a billboard of starving children in the Third World being papered over by Julie Christie’s plush lips, and later there’s a charity auction where black boys in white wigs and livery line the wall as well-stuffed socialites raise money for World Hunger relief, ignoring the racism at home while making their philanthropic gestures. (Sixties films were not Zen gardens of subtle ironies—when the charity’s president mentions the “agonies of malnutrition,” the camera cuts to some dowager helping herself to dainty sandwiches.) A study of upward drift from homey obscurity to a princess’s palace, Darling has an aloof integrity, declining to make Christie’s cipherish Diana Scott interesting or likable (it’s the male co-stars who provide the electrical juice, from Dirk Bogarde, nervously nursing some inward dissatisfaction, to Laurence Harvey, so thin, whippy, and sardonic, the transatlantic answer to Sweet Smell of Success); she’s a creature of caprice who gets a picture-perfect life only to find that it’s a joyless façade—a magazine cover with nothing inside. A movie essential, as they might say on TCM, Darling is a fairy tale gone sour where happily-ever-after turns out to be a sad letdown. Joanna, another prime entry, doesn’t deny its Kewpie-doll heroine—enacted by Genevieve Waite—a fairy-tale ending. It denies her nothing. Written and directed by Michael Sarne (whose next film would be Myra Breckinridge, not a happy advance for civilization), Joanna is besotted with its star, giving her so many puckish close-ups and costume changes that the filmmaking grammar breaks down, a very common occurrence in the anything-goes era, as if in this case the male gaze came unstuck and became a pair of ricocheting eyeballs.

The male gaze at its most brisk, workmanlike, and controlled is the perceptual driver of Michelangelo Antonioni’s flawed masterpiece Blow-Up where David Hemmings’s photographer, patterned on David Bailey and especially John Cowan, puts the models through their coltish paces, turning the once staid studio of fashion portraiture into a passion pit: most famously, straddling the model Veruschka as the lens of his clicking camera bores down like a phallic symbol so blatant that it provokes a knowing laugh, which doesn’t make the scene any the less audacious and legend-engraved. The most cerebral of London swingers, an existential mystery puzzle and rapt examination of fine bone structure, Blow-Up transcends the sociology of blithe hedonism to assign the male gaze a detective mission, a murder to solve. That the murder is never solved keeps the lid on the story unlatched, inviting endless re-investigative viewings, one of the many reasons it’s a classic. The graininess of film under enlargement reveals the dark matter swarming beneath the deceiving surface.

In many Swinging London movies the male gaze is hitched to a singular purpose—skirt chasing, pulling birds, however you want to slangily put it—and one of the shocks of seeing some of them again (and a few for the first time) is how sexually predatory they are, a lot of nasty, tactical gamesmanship operating under the guise of rakishness. Michael Caine’s Alfie in the breakthrough film of the same name, seduces and discards women or tolerates them as domestic appliances handy around the house, referring to this one or that one as “it,” eventually getting his jolting comeuppance and allowing Caine’s Cockney accent to crack sympathetically as he feels a lonely chill and wonders what’s it all about, Alfie. The System (released in the U.S. under the snappier title The Girl-Getters) and The Knack … and How to Get It make a marvelous pair of bookends for any misogynist’s mantel. Directed by Michael Winner, who would later deliver the vigilante justice of Death Wish on a buffet platter, The System is about a pack of prototype pickup artists who rack up as big a score as possible with the young lovelies who arrive in droves at the seaside village that is their stalking ground. (The posse’s leader is played by Oliver Reed, still young and capable of sensitivity before evolving into the glowering steamed crab of his more famous later roles.) Cinematically, The Knack is a far fancier juggler’s act, a whirling marriage of madcap absurdism and magic realism, but the underlying sentiments are strictly ugh. Its smart gleam in 1965 now looks like an icy leer.

Adapted from a play by Ann Jellicoe and directed by Richard Lester, coming off the bounce of A Hard Day’s Night, The Knack...and how to get it concerns a hapless celery stick named Colin (Michael Crawford) who has no luck with the ladies and requires the coaching assistance of a gloved roué named Tolen (Ray Brooks), whose regiment of interchangeable eye candy in tight white sweaters queues up the staircase to his apartment like an assembly line of ultra-white mannequins or returnable milk bottles. The Knack doesn’t merely depict objectification but colludes with it by offering us not a single female character with a functioning brain, the alternative to these buxom Barbies being a cawing, mannered Rita Tushingham, British cinema’s original manic pixie dream girl. After Tushingham’s Nancy falsely accuses Tolen, and later Colin, of rape, her parrot cry of rape! rape! rape! is treated as quirkily comical and theatrical—cute. (There’s actually an exchange when Colin tells Tolen, “She wants raping, so go in there and rape her!”) It is an indicator of how sensibilities have changed that the rape litany barely seemed to register with reviewers when the film was first released (“A splendid blaze of nonsense,” Newsweek hurrahed), and it even won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1965, perhaps a sign of how desperately with-it everyone wanted to be. The generation gap was widening with a vengeance, and nobody wanted to be on the wrong side and relegated to the scrapyard. Or bone heap.

A heavy whiff of fascism attended the rise to cultural power of teenyboppers and twenty-somethings and the emergence of the pop messiah. “We’re more popular than Jesus now,” John Lennon infamously told London’s Evening Standard in 1966, a comment that caused little stir in England but set off a fury here in the States, especially in the Bible Belt, where Beatles records and souvenirs were fed to bonfires, much as disco albums would be a decade later. The outrage couldn’t hide the panicky fear that perhaps pop stars really were the new apostles of an electronic religion that would exert control through the sheer force of demographics.

In Hollywood, this prospect bred the hysterically overwrought satire of Wild in the Streets, where the water in Washington, D.C., gets spiked with LSD and anyone over the age of 35 is rounded up and carted off into “rehabilitation” camps (including the pop star’s mother, played by Shelley Winters, who makes such a fuss).

While in London, the far grimmer Orwellian spectacle of Peter Watkins’s Privilege, where a pop idol (played by Paul Jones) is used by big meanies as an instrument of mass coercion. But the Swinging 60s were never really in danger of locking into a goose-step march. There was too much disarray, brain fry, and sullen withdrawal for a mass freak-out to solidify. By the end of the decade, Swinging London had folded its wings and abandoned the stage of the street for the refuge of the inner sanctum.

No movie serves as a better specimen jar for the rapid decay of grasshopper hedonism into mossy decadence than Performance directed by Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, an assaultive, immersive experience about a sleek, vicious London gangster (James Fox) who runs afoul of his boss and, after being savagely beaten in a scene that is a violent orgy of red paint, feathers, ripped fabric, smashed furniture, and shattered glass, as if an Action Painting had attacked itself, cons his way into a basement hideout hosted by an enigmatic figure named Turner, played by Mick Jagger at his lipsticked peak of androgyny. Turner’s lair is the infernal man cave and Moroccan drug den of a decadent dandy, a dream chamber where sexual identities blur, hallucinations bloom (courtesy of magic mushrooms), and no one ever comes round to tidy. It is like witnessing the birth of punk from the blighted womb.

Performance defies critical slotting as being good, bad, great, or god-awful—its grotesqueries and audacities trifle with all that. Charismatic in reptilian repose, Jagger is even more sensational unbound, tearing through the Memo from Turner number, and Anita Pallenberg suggests what might have happened to Julie Christie’s Darling had she dabbled in the satanic arts. Where have all the swingers gone? asked Mike Myers. Into the druggy dark below. Swinging London, like so much in the 60s, went to pieces. What’s missing is an interweaving saga that pulls the pieces back together, tracking the frisky freedom of the early, kicky days to the convulsive reckonings at the blowsy end of the decade and bundling it into a single epic." (Vanity Fair magazine)

SWINGING LONDON: THE FASHION TRENDS

"Perhaps nothing illustrates the new swinging London better than narrow, three-block-long Carnaby Street, which is crammed with a cluster of the ‘gear’ boutiques where the girls and boys buy each other clothing.” – Time Magazine April 1966

By the mid-1960's, London was teeming with baby boomers— 40 percent of the population was under 25. Such a society, driven by youth and unburdened with war, made London a fertile breeding ground for celebrity and pop culture, where such fashion icons including Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton and Jane Birkin rose to fame.

"The fashion revolution was all about the young crowd and started in the streets rather than the runway. Carnaby Street and Kings Road in London were the most popular places in England to shop, with Paraphernalia opening in 1965 in New York being the most famous in America. Pastels from 1950's fashions, gave way to bright, bold color often in geometric designs. Mod clothes leaned toward ultra-short and sleeveless. Popular styles were miniskirts, jumpers, shift dresses, patent rain trenches, patent leather go-go boots, and tights. A popular outfit was coordinating a ribbed knit turtleneck with a miniskirt with matching tights with knee boots.

The British domination of 1960's fashions also extended into hair styles, with Twiggy and Vidal Sassoon having a profound influence on short hair styles. But as with the mod motto of “anything goes”, it applied to hairstyles as well. The most popular hairstyle of the mod era was the bob. Cut short and blunt and stick straight, this haircut was the epitome of '60's mod style. Thick bangs were also a crucial part of this haircut.

Another popular haircut of the mod era was the "five point" Vidal Sassoon haircut, popularized by model Peggy Moffitt. This look was very similar to the bob - a short, angular five pointed pixie cut.

The hairstyle in vogue for men at the time was similar to that of mod women. Men sported a shaggy crop of hair or a short cut with a burned in part, much like that of The Beatles." (Fragrance XLibrary, Totally Mod: Fashion, Make-up, And Culture of the 60's)

Street Crowd Hanging out @ the Lady Jane Boutique

1966: John Paul, one of the owners of 'I Was Lord Kitcheners Valet' boutique

"In the mid-60's, Carnaby Street was where it was; Swinging London was in full force, and young people flocked to W1’s boutique-lined streets in the hopes of spotting a Beatle or a Rolling Stone while shopping for shorter hemlines and looser trouser legs. The Kinks actually wrote the song 'Dedicated Follower Of Fashion', poking fun at the "Carnebetian army" - the fashion victims who strutted through Carnaby Street. Shops like Lady Jane, I Was Lord Kitcheners Valet, and The Mod Male were popular hotspots for the capital's fashionable young things, while lithe model-types (hoping to emulate the popular ‘Twiggy look’ of the era) loitered on the street’s crowded pavements." (londonrockhistory.com)

"It was during the Swinging London era, that The Beatles, who had just opened a business entity known as Apple, branched out to include a boutique in London. The store was managed by Jenny Boyd, sister of Pattie Boyd, and Pete Shotton, who was John Lennon’s school mate. In addition to psychedelic and vintage clothing, the boutique sold books, music, spiritual objects, instruments and art. The concept of the store was that everything within it’s walls was for sale and was meant to capture the vibrant essence of the Fab Four and be a cultural centre for their friends and fans alike. Despite the overwhelming popularity of The Beatles at the time, the boutique was not ultimately a success for Apple Corps and had to shut its doors after only eight months. On closing day, The Apple Boutique opened up for the last time and decided to give away the remaining treasures within the store for free, on a one item per person basis." (flarestreet.com)

SWINGING LONDON: THE MUSIC

Along with the exciting changes in fashion, literature and film, it was the music that made London the pop music capital of the world. The "British Invasion" laid the groundwork which would go on to define London as the epicenter of pop music. The initial standout groups of this era were, of course, The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Dave Clark 5, The Kinks, The Who and The Animals. By the mid-sixties, the music lost much of its innocence as many songs were about the dissolution of society and its mores.

8 ESSENTIAL ALBUMS OF THE SWINGING LONDON ERA

THE BEATLES - REVOLVER (1966)

Most folks tend to lean on the Beatles' Sgt. Peppers album as their greatest effort but the way I see it, Revolver is their masterpiece. They work their way through an exciting investigation of varied genres and along the way reinvent rock & roll itself. It's an album that contains many guises and each time I listen to it, I hear things I never heard before.

"The rock historians often point to Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as the moment, in 1967, when rock magically grew up and became a legitimate art form, at least as it was perceived by the mainstream media. Many fans love the sprawl and variety of the self-titled 1968 double album, popularly known as The White Album. In some quarters there’s a fondness for Abbey Road and its side-long suite of mini-songs, and lovers of the Bob Dylan-influenced folk-rock of the mid-60's cherish Rubber Soul above all. They all have merit, but none of them is as consistently brilliant and innovative as Revolver.

It does everything Sgt Pepper did, except it did it first and often better. It just wasn’t as well-packaged and marketed. The hype that preceded Sgt Pepper had a lot to do with the leaps in imagination, the studio-as-instrument adventurousness, that flourished on Revolver in half the time: the sessions for the 1966 album spanned two-and-a-half months whereas Sgt Pepper took an unprecedented five months to record. Where Revolver began tells us a lot about where it ended up. When recording commenced in April 1966, The Beatles dived into the future with Tomorrow Never Knows. John Lennon conjured a sound in his head, and left it up to producer George Martin and a 20-year-old rookie engineer, Geoff Emerick, to figure out how to get it on tape. They succeeded spectacularly.

“He wanted his voice to sound like the Dalai Lama chanting from a hilltop," Martin later recalled. "Well, I said, 'It's a bit expensive going to Tibet. Can we make do with it here?'"

Lennon’s voice was filtered through a Leslie speaker cabinet, which gave it a vibrato effect normally associated with a Hammond keyboard. George Harrison brought Eastern drones to the track by playing a long-necked lute called the tamboura as well as a sitar, and Paul McCartney cooked up backward and vari-speed tape loops, including one that evoked the sound of seagulls. Ringo Starr’s drums were pushed to the foreground in the mix, inverting the typical hierarchy of most rock instrumentation. Ringo’s drums became the lead instrument, a thundering focal point amid the sonic chaos. Lennon’s ‘Tibetan-monk’ vocals urged listeners to "turn off your mind, relax and float downstream.”

All The Beatles’ previous albums had been rush jobs – their debut was recorded in 11 hours. But in 1966, the quartet pulled off the road for good to devote themselves to songwriting and record-making. Lennon and McCartney were still closely collaborating and pushing each other to new levels of innovation, and Harrison was emerging as a formidable third songwriter and voice in the band. Now, with the luxury of time to tinker, edit, re-edit and experiment, The Beatles were poised to record a masterpiece.

Tomorrow Never Knows set a high standard for an album that moves from one peak to the next: Harrison’s corrosive guitar lick and McCartney’s commanding counterpoint bassline in Taxman made for one of The Beatles’ toughest-sounding tracks, the brisk strings on Eleanor Rigby presaged the chamber-pop feel and emotional tenor of She’s Leaving Home on Sgt Pepper, and Harrison’s plunge into Eastern mysticism and modalities on Love You To set the stage for the similarly inclined Within You Without You on the later album.

The melancholy beauty of Here, There and Everywhere answered the challenge of Brian Wilson’s Beach Boys masterpiece Pet Sounds, Doctor Robert and And Your Bird Can Sing achieved jingle-jangle guitar-pop perfection, and the horn-fueled Got to Get You Into My Life channeled Motown and Stax soul. Even a relatively lightweight track such as Yellow Submarine presaged the sometimes fanciful, almost child-like wonder of Sgt Pepper tracks such as Lovely Rita.

Sgt Pepper proved to be a prettier package, with its elaborate Peter Blake cover art of the satin-suited, newly bearded Beatles among images of cultural icons ranging from Karl Marx to Mae West. The Beatles spent 700 hours in the studio crafting it, but despite its unassailable high points – the staggering A Day in the Life, the acid-rock fantasia Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds – it’s also riddled with the cute and lightweight (When I’m 64, Lovely Rita) and the drab (Within You Without You).

Revolver was preceded by Rubber Soul, recorded in 1965, in which the band had achieved a new level of sophistication in its songwriting. The evocative wordplay in Norwegian Wood and In My Life aspired to the pop poetry of Dylan and Smokey Robinson. Song for song, it matches up well with Revolver, but it’s not nearly as sonically ambitious....Revolver wasn't always so highly regarded. A few months after it was released, The Beatles began recording Sgt Pepper, an event that was chronicled with great fanfare as the band sequestered themselves in Abbey Road studios. Its magnificence seemed a fait accompli. In contrast, the release of Revolver was overshadowed by Lennon’s infamous and widely misinterpreted ‘more popular than Jesus’ comments. But time has affirmed the enduring worth of Revolver. It now stands as The Beatles’ greatest album." (Greg Kot; BBC.com)

THE KINKS ARE THE VILLAGE GREEN PRESERVATION SOCIETY (1968)

I have always felt that the Kinks were deserving of the same lavish praise that's been heaped upon the other stalwarts of the British Invasion era (i.e. The Beatles, The Stones& The Who). Sadly, this is not the case. Has England produced a true songwriter better than Ray Davies? I think not. To make the case that The Kinks should rightfully be ranked alongside The Beatles, let me put forth a hot platter that is as strikingly inventive as Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Yes, friends, I speak of (fanfare please) The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society!

Released in 1968, this concept album paid tribute to the simpler days of English small-town life and all of its daily minutiae. It is a collection of songs about friends, childhood memories and family. While some of these themes had been artfully explored on the Sgt. Peppers album, Ray Davies ability to communicate a certain sense of British sensibility was a bit more striking than what Lennon & McCartney had created on Sgt. Peppers. As Chuck Berry's songs were uniquely American, The Kinks, with the release of this hot platter (and their opus "Waterloo Sunset"), had become the true ambassadors of the English perspective, both old and new.

I think this particular album is often overlooked when compared to the triumphs of The Beatles during Swinging London years. Aftermath, an album which was a first in that it was comprised of all original material for the first time, reveals the Stones moving past their dependence on the blues genre and 50's rock & roll. The Jagger/Richards songwriting team was obviously stretching out into new territory. Along with what the songwriters were coming up with was complimented by Brian Jones' adroit command of many differerent instruments such as a marimba, a sitar and a mellotron.

“By 1966, rock ’n’ roll albums were becoming deep. Where LPs were once merely collections of a few singles, fleshed out with some cover songs, they were increasingly treated as cohesive long-form works in and of themselves. Aftermath, the first Stones album to consist of all Jagger/Richards–penned songs, was also their first record that felt like an organized and focused project. As the LP was fast becoming the medium of choice for established artists looking to make an impactful statement, it also allowed for quieter moments like the Aftermath deep track, I Am Waiting…Judging from the material on Aftermath, the Stones’ beer-and-blues days at the Crawdaddy, only three years prior, had slipped into what must have seemed a distant past. ‘One part of their souls resided in a bizarre re-visitation of Baudelairean nineteenth-century debauch and baroque,’ Oldham wrote of the 1966 period of the Stones, the other in a Neanderthal, pretentious, psychedelically entitled, and tripped-out world.” (Bill Janovitz, Rocks Off; St. martin’s Publishing Group)

THE WHO - THE WHO SINGS MY GENERATION (1965)

As stated here before on this blog in a previous blog post titled My First Rock Concert, The Who were the first band to capture my imagination. They had it all; power chords, an avalanche of drum fills, feedback guitar and an anthem called My Generation. Shel Talmy, a well-known producer back then, captured the band’s visceral style perfectly on their debut album. The album sports a collection of tasty Pete Townshend power pop tunes that defined their early style best described as Bang! Bang! Zoom! Boom!

THE KINKS - FACE TO FACE - THE KINKS (1966)

By 1965, Ray Davies (The Kinks’ mastermind songwriter) had established himself as a major songwriter with such classic songs as A Well Respected Man and Dedicated Follower of Fashion which were a far cry from the band’s earliest triumphs You Really Got Me and All Day and All of the Night. By this time in the band’s career, Ray Davies began to write material about social pretensions in the British society.

"Face To Face, along with the following three Kinks’ releases, was a byproduct of this newly adopted motif. Not as immediately accessible as the power-chord blasting, heavy-hooked singles of the past, the songs on Face To Face grow on you gradually, relying on the listeners’ intellectual participation, rather than a visceral response, which makes them ultimately more enduring. Lyrically the album serves as the master’s class of bourgeois character studies. On every track Ray Davies’ wry smile and cocked eyebrow are almost audible. Eventually becoming the profligate wastrels that the band once skewered, in 1966 The Kinks still thought of themselves as working-class Muswell Hill yobs taking the piss out of posh strangers who wandered into their pub." (popstache.com)

THE ZOMBIES - ODYESSY AND ORACLE (1968)

I discovered this magical album after reading an article in Crawdaddy Magazine that featured Al Kooper raving about how good it was.

"Fate conspired against the making, release and success of Odessey & Oracle. Recorded amid the acrimony of a band imploding, this was the Zombies’ first and last album. Their previous two LP’s; shoddily assembled singles collections issued without the band’s input, and sinfully excluding many of their finest B-sides, had sold poorly. By 1967, after having been conspicuously absent from the Top 40 for over two years, the Zombies truly were the walking dead. They entered Abbey Road Studios in June of that year resigned to the fact that this would be their final record. It was the album of a fractious, defeated band with nothing to prove but plenty left to give, recorded on a meager budget provided by a label who’s indifference was so absolute that it didn’t even proofread the album art (no, the misspelling of Odyssey was not an intentionally trippy 60’s thing). It languished in the CBS vaults for nearly a year before Al Kooper, then an A&R rep for CBS, could persuade an unimpressed Clive Davis to even release it. Despite the inclusion of the biggest hit of the Zombies career (Time Of The Season), Odyssey & Oracle, to nobody’s surprise, was a commercial and critical disappointment. Now widely considered one of the great, lost masterpieces of the psychedelic era, Odyssey & Oracle sounds timeless and ethereal. Awash with lush harmonies, florid piano, majestic mellotron, swirling organ and shimmering guitar, it is a chamber pop honey hole." (popstache.com)

THE BEATLES - SGT. PEPPERS LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND (1967)

The release of The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album brought about a sea change in the approach musicians were taking in recording their albums. For a time, many bands released albums that reflected a conceptual element that revealed what was on the minds the youth culture. After their Revolver album release, The Beatles stopped touring so that they could have more time to work in the studio on their latest masterwork. The Sgt Peppers album allowed the Beatles to recreate themselves by creating an album that featured “a performance by the fictional Sgt. Pepper band, an idea that was conceived after recording the title track, and incorporates a range of stylistic influences, including vaudeville, circus, music hall, avant-garde, and Western and Indian classical music.” (Wikipedia) The Sgt Peppers album broke new ground in many ways; the album cover set a new bar in its artistic expression and the album was one of the first to include song lyrics.

"If, as some have said, Revolver is the Godfather of pop music then Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is, inarguably its Citizen Kane; brashly self-confident, startlingly innovative and eternally influential. Ensconced in the Abbey Road studios for, a then incomprehensible, 129 days, each band member accepted his role dutifully: George Harrison continued his dalliance with Vishnu on Within You Without You, John Lennon gleaned sardonic inspiration from newspaper headlines (A Day In The Life), circus posters (Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!), a child’s doodles (Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds) and breakfast cereal commercials (Good Morning Good Morning); Ringo Starr stood loyally by awaiting his assignments (playing the role of Billy Shears in the title track and its reprise) and Paul McCartney tried in vain to preserve the confluence of what began as his Edwardian music hall concept album. Retrospectively regarded as the harbinger of the summer of love, it was the first Beatles record to cop to the rumor that the band was indeed… British! No longer content with pandering to American sensibilities, they instead provided us with a collection of short stories vacillating between the celebration and indictment of middle-class English life, laced with references of a colorful double-decker bus, the Albert Hall, the Isle Of Wight and, of course, cups of tea." (Alllen Trenton, Beatles Unlimited; Mystery Trend Publishing)

THEM - THE ANGRY YOUNG THEM

"Everybody wants to be Irish on St. Patrick’s Day, and everybody wanted to be British during the British Invasion, even the Irish. Them was a band that melded the rawness of the blues with the surliness of Northern Ireland. With rock ‘n’ roll’s perennial kelly-green curmudgeon, Van Morrison, on vocals and a blunt, no-nonsense approach, they indoctrinated a generation of garage rock bands to the joys of pop primitivism.

Angry Young Them, the U.S. version of the band’s self-titled debut, is superior to the U.K. release because it includes and opens with the fantastic Bert Berns written Here Comes The Night, relegating the chaotic, impromptu studio jam Mystic Eyes to track two. The highlight of the album specifically, and rock ‘n’ roll in general is, of course, Gloria, a song so perfect that it may be the only human creation spared by the machines after singularity occurs.

Due to the machinations of the band’s meddlesome label, after this release Them was torn apart and reassembled several times during its short lifespan, Morrison being the only recurring member. The following album, Them Again was ostensibly a solo Van Morrison record with studio musicians, including gun-for-hire Jimmy Page, supporting him. One can only speculate on what they might have accomplished if left grow unimpeded by the suits." (popstache.com)

In closing, let me say that this blog post brought back many memories. In 1965, I moved to France with my family which came about because my father was an Army doctor who got stationed over there. In '65, my Dad took us on a trip to London. Looking back, I can't believe I actually got to see the epicenter of Swinging London. While there, I managed to talk my folks into letting me go down to Carnaby Street with my brothers. There was an intensity out on the streets of London then (just as I've described in this blog post). I ended going into several stores on Carnaby Street and ended up buying Bullseye t-shirt (as popularized by Keith Moon of The Who) and a pair of Beatle boots that didn't quite fit me. As I left the store and was walking down the street, I saw this huge poster on a brick wall...

I stood there for the longest time just staring at the image of Pete Townshend on the poster. When I returned to France, I managed to convince my parents that I desperately need an electric guitar. Within another month, I had joined a band and was performing at various clubs. I later realized that when I stood before that poster of Pete Townshend on Carnaby Street that day, I had decided that Rock & Roll had become my State of Mind.