Today we're going to take a look at

what goes on during Mardi Gras!

The holiday of Mardi Gras is celebrated in all of Louisiana, including the city of New Orleans. Celebrations are concentrated for about two weeks before and through Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday (the start of lent in the Western Christian tradition). Usually there is one major parade each day (weather permitting); many days have several large parades. The largest and most elaborate parades take place the last five days of the Mardi Gras season. In the final week, many events occur throughout New Orleans and surrounding communities, including parades and balls (some of them masquerade balls).

Carnival, the riotous and bawdy festival celebrated across Europe and in the Southern region of the United States, has been in existence almost since the beginning of civilization itself.

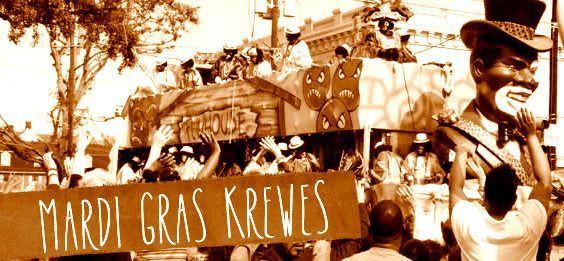

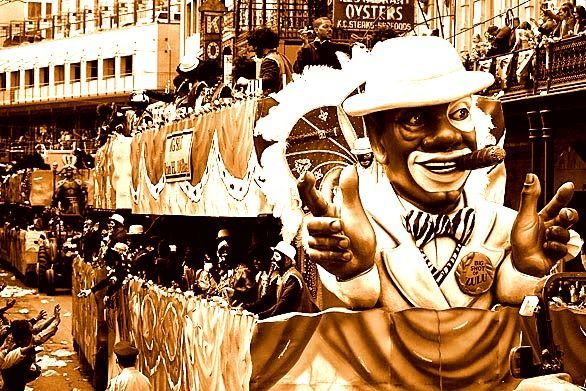

The parades in New Orleans are organized by social clubs known as krewes; most follow the same parade schedule and route each year. The earliest-established krewes were the Mistick Krewe of Comus, the earliest, Rex, the Knights of Momus and the Krewe of Proteus. Several modern "super krewes" are well known for holding large parades and events, such as the Krewe of Endymion (which is best known for naming celebrities as grand marshals for their parades), the Krewe of Bacchus (similarly known for naming celebrities as their Kings), as well as the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club—a predominantly African American krewe. Float riders traditionally toss throws into the crowds. The most common throws are strings of colorful plastic beads, doubloons, decorated plastic "throw cups", Moon Pies, and small inexpensive toys, but throws can also include lingerie and more sordid items. Major krewes follow the same parade schedule and route each year.

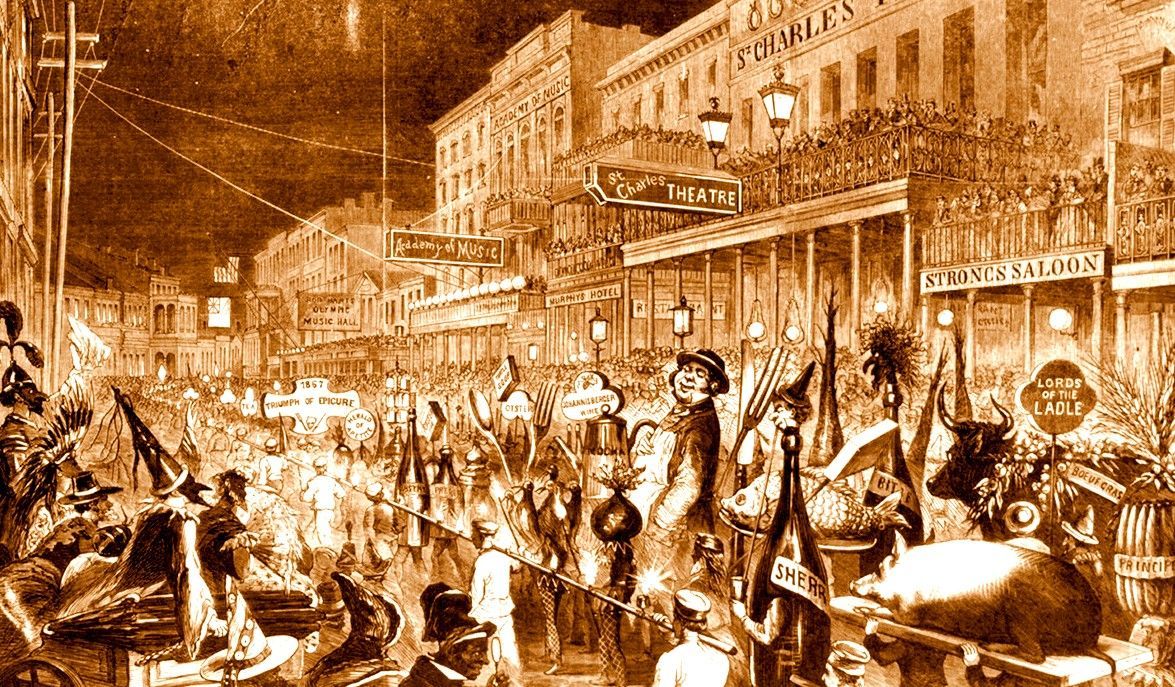

By 1837, unofficial parades were held in the streets of various southern cities. By 1872, the Krewe of Rex held their first official parade. The parade was in honor of the visiting Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. It is here that the official colors of Carnival were instituted. The Krewe of Rex chose the royal colors of the Romanoff family of Russia as their backdrop. This choice of colors continues to be used to this day. The colors are purple which stands for justice, gold for power and green for faith.

MASKS & COSTUMES

"Masks and costumes have been associated with Shrove Tuesday celebrations for centuries. And even today of the masks commonly seen in New Orleans on Mardi Gras are the same types popularized by the two-to-three-week-long Carnivale in Venice that culminates with Fat Tuesday. But masking and costume-wearing in New Orleans also has a specifically American history, as it was another way for revelers who were officially excluded from the festivities to join in, by concealing their identities. This phenomenon was particularly pronounced during the Jim Crow era of the early 20th century. For example, the African-American men now known as Mardi Gras Indians first paraded down the city’s back streets in Native American costumes, in a nod to Native Americans who took in and protected runaway slaves. Another poignant example, the breaking of the Race and Gender Barriers of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Tradition, can be found in the African-American prostitutes who dressed up as Baby Dolls — a persona chosen because that’s what male clients called them — in hopes that the costumes would help them land work at a time when sex work was racially restricted. Legend has it that the custom of throwing Mardi Gras beads from parade floats started sometime in the 1880s when a man dressed like Santa Claus was cheered when he tossed some beads into the crowds along the parade route. In short order, other Carnival Krewes adopted this popular Mardi Gras tradition. The throwing of beads and fake jewels, from parade floats to those watching down below, is thought to have started in the late 19th century, when a carnival king threw fake strands of gems and rings to his “loyal subjects” sometime in the 1890s. By the early 1920s, one of the Krewes, probably Rex, started regularly throwing strands of glass Czech beads, a precursor to the plastic beads seen today. Other throws — such as doubloons marked with the names of the krewes that make them — followed after." (The Culture of Mardi Gras)

BEADS

“Though there’s some debate over the extent to which ancient beads are evidence of advanced syntactical language, the cross-cultural importance of beads goes so far back that much of its meaning has been lost to time. Since antiquity, humans have used beads to reflect cultural identity and social status. Fast forward to today—and today, specifically, being Mardi Gras—and New Orleans is arguably the planet’s most bead-drenched city. (The environmental implications, it seems, are no match for tradition. Mardi Gras has been called the season of madness in New Orleans. The ritual of Mardi Gras has survived Hurricane Katrina, Prohibition, and the Civil War, but its roots go much deeper than that. The earliest Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, an import from France, date back to the 17th century. The first krewe, the local term to describe the clubs that organize Mardi Gras festivities, was founded in 1858. By around 1870, krewes were throwing trinkets, baubles, and candies to crowds during parades. A decade later, they were throwing medallions. Beads occupy a paradoxical space at today’s Mardi Gras celebrations. They can be both the centerpiece of festivities and the trimming. They’re prized objects, and yet many strands of beads—or pairs, to use the proper New Orleans lingo—are discarded, metallic snakes left curled in gutters. They’re simultaneously coveted and cast aside. Strands have become longer, in general. Machine-made beads largely replaced hand-strung beads. Glass was replaced with plastic. Opaque plastic medallions gave way to transparent plastic ones. Medallions gradually got bigger and bigger. Most recently, beaded strands for medallions have been swapped out for satin cords. These details all factor into a deeper understanding of a celebration that’s, for all its lunacy, much more complex than it may appear. Mardi Gras beads, to the uninitiated, are just chintzy party favors doomed for the landfill. But they’re also a link to the past, a symbol of a celebration that’s been going on for as long as recorded history.” (The Atlantic)

The Krewe of Rex was the first carnival krewe

to throw trinkets to the crowds during a street parade.

This event also marked the premiere of the official Mardi Gras song,

If Ever I Cease To Love.

If ever I cease to love, if ever I cease to love

May the moon be turned into green cheese

If ever I cease to love

During the 1800's and 1900's, many Carnival Krewes came into existence; along with walking clubs and Social Aid and Pleasure clubs. These clubs existed for the purpose of parading, having fun and helping their communities through various charity efforts. In their earliest days, Krewes were dignified and very serious about their procedures, parades and the themes behind their parades. Majestic and historical themes were commonplace as the Krewes treated their subject matter with elegance to their celebrations. One of the first of these types of Krewes was the Zulu Krewe. Throughout the years, however, the newer Krewes took more of a tongue-in-cheek approach to all things Carnival.

In the early 1900's, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure club made its mark on Carnival. Zulu was comprised entirely of working class black Americans. In their parade, they mocked the snobbishness of Krewes like Rex and Comus. In fact, their parade float was a comical caricature of the Krewe of Rex. Instead of masking in the royal colors of Rex, the members of Zulu wore blackface. When the Zulu tradition began, the Zulu King wore a crown made out of an old can of lard as opposed to the bejeweled crown of King Rex. The Zulu Queens were all men dressed in drag and the royalty of Zulu sported names like the "Big Shot of Africa." Zulu was also the first Krewe to connect the marching band street jazz sounds of the black neighborhoods to the Carnival Season.

This 2006 Washington Post article describes how the true spirit of Mardi Gras continues to endure into the New Millenium: "What's remarkable about Mardi Gras in New Orleans is the extent to which the entire city has institutionalized this defiant laughter, so that every class, race and condition shares it. In a noisy, messy, highly varied and inevitably imperfect way, Mardi Gras amounts to all New Orleanians reminding each other that they're all in this fate thing together. Nothing signals that more than the climax of Mardi Gras, just before it all ends tomorrow, when Comus, the symbolic king of New Orleans's vestigial old family aristocracy, and Rex, the "king of the people," ceremonially come together at the end of their krewes' elaborate balls at New Orleans Municipal Auditorium...But the point is that carnival isn't just about having a good time. It's about reCarnival is very much a cultural and psychological survival mechanism for almost all New Orleanians, black and white, rich and poor, and for the city as a whole. It's the great shared experience of perhaps America's most culturally diverse city -- a giant municipal block party in which each neighborhood, age and ethnic group acts out and shares with others its particular finger-at-fate coping mechanism, minding oneself that good times are a precious part of life -- not to be traded casually for an extra hour at the office or a fleeting illusion of power or significance."

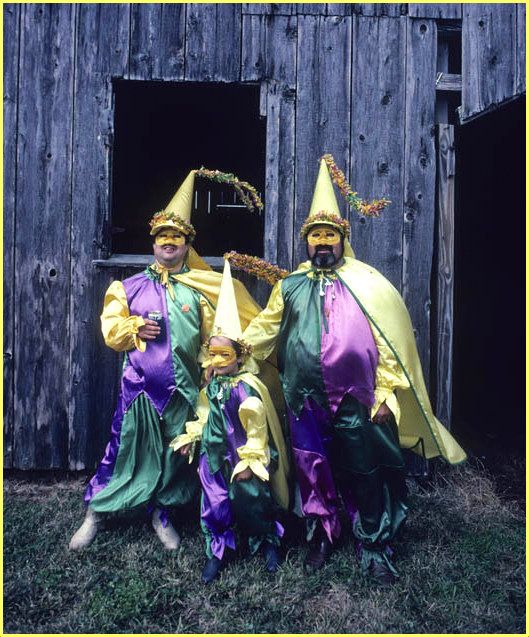

CAJUN MARDI GRAS

The Courir de Mardi Gras (literally to “run” Mardi Gras) is a rural and lesser-known Cajun counterpart to urban celebrations of Fat Tuesday in such cities as New Orleans and Lafayette. For the courir, disguised revelers convene before dawn at a predetermined locale, typically a participant’s farmstead. They form a costumed band that travels either on horseback or by tractor-drawn trailers throughout a rural community, calling on neighbors, relatives, and friends. Playing the dual role of a jester and beggar, the revelers sing, dance, and perform comic antics in exchange for “a little fat chicken,” guinea hens, rice, sausage, onions, or lard—all ingredients for a communal gumbo that is served later that evening. Fowl are generally donated alive, requiring revelers to chase and capture chickens and guinea hens. The tradition functions as a ritualistic means of creating, sustaining, and defining the boundaries of rural communities in southern Louisiana.

Though there are approximately thirty versions of the courir de Mardi Gras, the celebrations can be distinguished by the participants’ method of travel. While some runners travel on horseback, others ride on tractor-drawn wagons, and a few use a combination of horses and wagons. There are all-male, all-female, mixed gender, and—most recently—all-children runs. The use of whips constitutes perhaps the most striking difference among the revelers. In whipping celebrations such as those in Tee Mamou, l’Anse LeJeune, and Hathaway, captains wield thick, braided burlap whips to keep order. Scholars believe the whipping ritual descends from a pre-Christian festival known as Lupercalia, in which participants would run past bystanders, whipping them with a goat skin thong as a fertility demonstration. Some revelers willingly endure the whippings, which are not violent in nature. In others, part of the tradition includes attempts by the runners to take the whip away from the captain.

Both all-female and all-male runs are led by unmasked male capitaines. The men often wear a cowboy hat or baseball cap while carrying flags symbolizing their authority. Capitaines act as mediators between the Mardi Gras runners and the community. In exchange for providing entertainment for the community, they procure ingredients for the gumbo. Moreover, it is the capitaine’s responsibility to assure homeowners that the revelers will not steal from them or damage their property.

Singing is another important component of the rural Mardi Gras celebration, and two basic variants are found in celebrations across Acadiana. The first type—lyrics sung with instrumental arrangement—is organized with a minor modal chord progression. These songs describe the characteristics and purpose of the Mardi Gras run: “We get together once a year, to ask for charity/Even if it is just a skinny chicken, or three or four ears of corn.” The song concludes with an invitation to “join us for gumbo later tonight.

A number of Cajun musicians—including the Balfa Brothers and Nathan Abshire—have recorded different versions of this composition. The second song variant is a French drinking song that is performed a cappella as revelers approach a home. In the Tee Mamou Mardi Gras, for instance, approximately ten people line up shoulder to shoulder over several rows and sing the song while slowly creeping toward their neighbor. This particular variant describes a dwindling bottle of alcohol.

Joy of heart, good cheer and merriment

are wine drunk freely at the proper time."

The Bible, Sirach 31:27

Also if yer still hungry for some New Orleans vibe

then start making plans to go to the

NEW ORLEANS JAZZ & HERITAGE FESTIVAL

APRIL 25 Thru MAY 5

Life Is Short…So Have Some Fun Why'doncha!

If Yer In A Mardi Gras Mood

Check out our new Mardi Gras Music page!

This tune which was created by

Haiku Monday is full of energy!

This track is part of Haiku Monday's album, The Ghost of Pontchartrain Expanded Edition that features a unique solo performance by Alex Maes, the band's guitarist.

Here's a sweet jazz tune as played by Nick Sassone, a brilliant jazz artist.

It's time to Swing the good thing!

As darkness begins to fall on New Orleans The Ghost has begun to cause havoc.

The Spy Boy gets ahead of the Indians and gets them ready for the upcoming shakedown against another Indian tribe. Yeah you rite!

Check out The Hideaways as they groove into a cool Hank Williams tune as Mardi Gras is alive!

As the Mardi Gras Parades went by, the days were filled with memories.

A wild breakout of blues sounds from the Mighty Young Fish!

Something Happened when the sun went down and the Mardi Gras revelers woke up in Whiskey Town...

Walking in a New Orleans graveyard is always a challenging way to spend a night.

Dr. John sez,

“Yeah! You Rite!”