It's time for Part 2 of Lost Albums of the 1970's as we take a look at some of the wonderful "Lost" albums of the 1970's. There were many excellent records that popped up on my radar whenever I would go through the album racks in various record stores during this particular rock & roll era. As a matter of fact, many times I would discover some very unique and special albums in the $1.00 bins.

Most of the albums in today's post entered my life while I was attending college at the University of Dayton. At times I found myself lost in the Mid-West but as soon as I discovered some of the excellent record stores I felt like I belonged in Dayton.

Anyhow, without further adieu, let's check out some more great lost albums of the 70's!

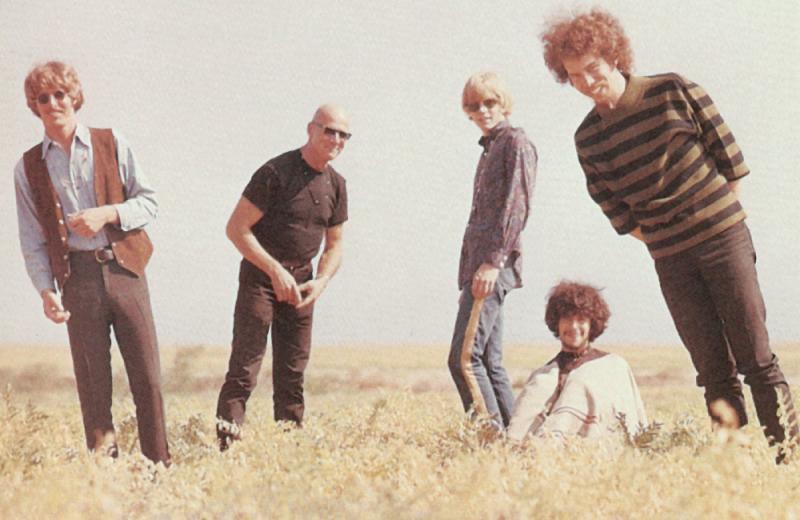

Spirit - Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus

Spirit's Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus was one of my favorite albums that I listened to during my Sophomore year of college at The University of Dayton. At the Student Union there was a music listening room which was where I first heard this wonderful slab of vinyl.

Producer David Briggs

In 1968, after picking up a hitchhiking Neil Young, David Briggs went on to produce the singer-songwriter's first solo album, entitled Neil Young (1968). This led to a lifelong friendship between the two men, with Briggs co-producing over a dozen of Young's albums including Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and After the Gold Rush.

Working for the first time with Neil Young’s producer David Briggs, the band delivered an adventurous suite of songs – a concept album that marks the shift from psychedelia towards prog-rock. The literary and philosophical themes of the record’s intelligent lyrics avoid the usual prog-rock clichés however, and the record has often been cited as an early example of art-rock. An album of unexpected twists and turns from gentle folk-tinged balladry to heavy rocking, riff-laden prog and Zappa-esque experimentalism, guitarist Randy California’s playing throughout is a particular highlight.

Working for the first time with Neil Young’s producer David Briggs, the band delivered an adventurous suite of songs – a concept album that marks the shift from psychedelia towards prog-rock. The literary and philosophical themes of the record’s intelligent lyrics avoid the usual prog-rock clichés however, and the record has often been cited as an early example of art-rock. An album of unexpected twists and turns from gentle folk-tinged balladry to heavy rocking, riff-laden prog and Zappa-esque experimentalism, guitarist Randy California’s playing throughout is a particular highlight.

Spirit - Nature's Way

The original release of the Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus , which was the Spirit's 4th album, was initially released in 1970 on the Epic label and peaked at number #63 on the Billboard charts. While the album wasn't a smash hit, the album became the band's only album to ultimately attain a RIAA gold certification in the U.S., achieving that status in 1976. Due to the popularity of underground radio, the album began to have a second life with many rock afficionados.

"Although Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus has the reputation of being Spirit's most far-out album, it actually contains the most disciplined songwriting and playing of the original lineup, cutting back on some of the drifting and offering some of their more melodic tunes. The lilting Nature's Way was the most endearing FM standard on the album, which also included some of Spirit's best songs in Animal Zoo and Mr. Skin." (All Music, Richie Unterberger)

Gene Clark - No Other

Gene Clark, who started out in the music business as an original member of The Byrds, was a "rock star" who was known for his stage fright whenever he had to appear before an audience. After leaving The Byrds, Clark embarked on a solo career. No longer able to disappear into a band situation, Clark was never able to develop a solid career as a solo artist. Gene Clark's solo career always seemed to have a deer in the headlights quality.

"Clark's albums under-performed while covers of his songs sent the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt towards superstardom. The Byrds’ 1973 reunion album on David Geffen’s Asylum Records was an all-out critical and commercial disaster, but it was Gene who emerged from the wreckage with the album’s strongest songs and performances, to the point where Geffen gave him a recording budget of $100,000 to realize his masterpiece in 1974. For one glorious moment, it seemed that Clark’s solo fortunes had finally turned, and you can hear almost every single one of those dollars poured into No Other, a deliriously opulent, rococo work in a decade filled with them. But when it was time to play the album for Geffen, he took one look at the eight songs on the vinyl and yelled at Clark: 'Make a proper fucking album!', throwing the test pressing in the garbage without even listening to it. No money would go to promote the album and No Other tanked, all but ending Clark’s career. One of the most exquisite spiritual seekers in song, Clark was dead by the age of 46, ravaged by alcohol and heroin."

Gene Clark - No Other (remastered)

From UNCUT magazine:

"No Other...came out of a meditative period – talking about the writing process, Clark told Paul Kendall in 1977, 'I would just sit in the living room, which had a huge bay window, and stare at the ocean for hours at a time… In many instances with the No Other album, after a day of meditation looking at something which is a very natural force, I’d come up with something.' No Other is wide-eyed, unwieldy at times, awash with gospel backing vocals, swirls of keening strings, a hybrid monster voraciously swallowing genres – no surprise, really, given Clark later said the album was influenced by two similarly catholic sets, the Stones’ Goats Head Soup and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions.

Life’s Greatest Fool opens No Other, its lilting gait and countrified melancholy soon cleaved apart by a soaring choir, rising from the song with breathless intent. Silver Raven glitters, an incandescent light shimmering through its liquid languor; No Other itself is a late-night reverie, a down ’n’ dirty dirge, an epically over-fuzzed bass rutting its way through the song. Some Misunderstanding is Clark at his most tender, and accordingly, the song’s verses are open and spacious; in the chorus, this most questing of lyrics is undergirded with rattling organs and swooning gospel singers.

There are moments of gentleness, like the sweet country soul of The True One, perhaps the most straightforward number on the set. Throughout, though, No Other plays deceptively, a complexly structured beast that manages to feel loose, funky, vibrant, sometimes swampy, sometimes epic, no more so than on the cosmic dialectics of Strength Of Strings, its centerpiece, a stirring hymnal lost in its own reverie, nimble bass plumbing the depths while tremolo slide guitar and clusters of chordal piano corral around one of Clark’s greatest vocal performances."

As time rolled on, Gene Clark's songs influenced the music of the likes of Fleet Foxes and Father John Misty.

The Beach Boys - Surf's Up

The Beach Boys' Surf's Up album was a moment in time circa 1971. Surf's Up seemed to put away the styles of their earlier albums as the band moved forward. My quota of listening to the Surf's Up was enhanced by catching the band live at a venue in Cincinnati, Ohio. Seeing the band live reinforced how brilliant the this album really was. While the Surf's Up album received positive reviews in various rock magazines, I can recall sensing that the broad collective of music fans still seemed to view The Beach Boys as old hat. This album clearly proved that The Beach Boys had captured the magic once again!

Surf's Up is filled with songs that deal with environmental, social, and health concerns rather than produce more songs about surfing and fun times at the beach. This came about due to the efforts of the band's newly recruited co-manager Jack Riley, who convinced them to alter the band's image. Riley came up with a promotional campaign that stated that 'it's now safe to listen to the Beach Boys' and the making of Carl Wilson as the band's official leader which led to Carl Wilson's first major song contributions; Long Promised Road and Feel Flows.

The Beach Boys - Surf's Up (full album)

From Udiscovermusic.com:

"Surf’s Up is rightly remembered for Brian Wilson’s brilliant double-header that closes the album, ’Til I Die and the title track collaboration with Van Dyke Parks, filled with its enigmatic lyrics and stirring harmonies. But just as remarkably, the album showcased a group with multiple writing teams, all bringing excellent work to the table.

Mike Love and Al Jardine contributed an opening song with an anti-pollution lyric that was really ahead of its time, Don’t Go Near The Water. Carl Wilson and Riley completed Long Promised Road and Carl’s sweet voice led his own Feel Flows. Al and Gary Winfrey added the short, equally relevant Lookin’ At Tomorrow (A Welfare Song), the pair working with Brian on Take A Load Off Your Feet.

Bruce Johnston’s writing contribution was the magnificent Disney Girls (1957), while Brian and Riley composed the plaintive A Day In The Life Of A Tree, on which the group’s manager also sang. There was even room for Mike Love to sing his adaptation of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller’s Riot In Cell Block No.9, which he renamed Student Demonstration Time for the social situation of the day."

Brian Wilson in the studio during the Surf's Up sessions

Surf's Up endures to this day thanks to the beautiful mini-symphonies like ’Til I Die and Surf's Up, the album's beautiful title track.

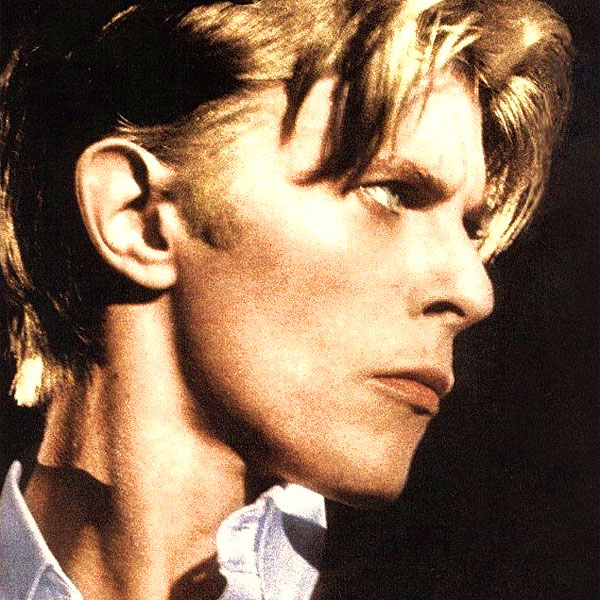

David Bowie - Low

This startling album came rolling out of David Bowie's imagination in 1977 and, as with all great masterpieces, it took decades to cement itself into the rock & roll culture. Low was the first album in what would become David Bowie's Berlin Trilogy. After going wild with a cocaine habit in Los Angeles, Bowie eventually realized he wouldn't survive if he continued this dangerous lifestyle so he planted himself (with Iggy Pop) in a studio in France and then finally settled in Berlin Germany to detox his imagination. Berlin became the place where some of his most creative (and bizarre) music was made.

David Bowie - Low (full album)

This instalment of the Berlin trilogy is widely thought of as the most aligned with the era’s pursuit of experimentation. With Bowie kicking his cocaine habit into touch and the star trying to reinstall a sense of creative curiosity, Low is a joy to behold as he traverses the pitfalls of modern life.

As Bowie began to employ the William S. Burroughs cut-up technique for writing lyrics, the music and the output became more and more opaque. More dense and textured. Bowie had been experimental before, but now it was a deliberate pursuit, and on Low, he delivers experimentation with a cheeky wink and a glint in his eye that confirmed he was one of the greats before anybody had asserted him as so.

Tony Visconti captains the ship on production, and the album moves like a well-oiled machine because of it. Of course, Brian Eno is also on hand to lend his help where needed. It’s a dream combination that ends up in an ethereal album that seemingly creates its own world for you. However, despite being one of Bowie’s more obscure records, it contains one of his most potent pop songs, ‘Sound and Vision’.

Sound and Vision remains one of Bowie’s most notable songs. A permanent fixture in some people’s top ten lists, the song is an archetypal piece from the Thin White Duke as he uses abstract lyrical constructs shaped by incessantly groove-filled instrumentals to bamboozle and entrance.

The song had originally been composed as an instrumental track, something Visconti and Bowie had agreed upon when creating the Berlin trilogy LP but was soon flourished by some of the singer’s more abstract lyrics. It’s a song that showed Bowie was always an artist before he was a pop star and, when it could’ve been so easy to conform and write pop ballads forevermore, he showed that artistic evolution was always paramount.

Across the rest of the album, there are joyous moments, Subterraneans is still a vital piece of Bowie’s iconography, as is New Carrer in a New Town and Always Crashing in the Same Car. However, to focus too heavily on individual songs is to undercut the point of the album. Bowie was sick of writing rock and pop songs for the charts. He no longer wanted to behave in the ways the audience wanted him to. In truth, Low was Bowie’s refusal to play to the gallery, even if it did begin to put the spotlight on him in a brand new way.

Low won’t be for everyone, but if you can make an album like this, under the pressures Bowie was facing, and have it still sound as potent and perfect 45 years on from its release, then you’ve surely achieved something. For the man who achieved pretty much everything that he set out to do in his career, no album speaks as loudly of Bowie’s credentials as Low.

From pitchfork.com:

"The first album in David Bowie's Berlin Trilogy sees Bowie as a tragic figure. The album's first side is a beautiful futurist ruin, littered with holes left purposefully unfixed, while the blank, instrumental second side feels like a calculated attempt to kill the author.

Compared to its predecessors, David Bowie's 11th studio album is noticeably reserved. 'I had no statement to make on Low,' said Bowie, who could hardly write lyrics at all in the aftermath of his L.A. excesses, let alone fashion another extensive character study like Ziggy or the Thin White Duke. His lyrical gifts were already spread thin, and thinner still when a completed third verse was cut from Always Crashing in the Same Car, in which Bowie did his very best Bob Dylan impression. Producer Tony Visconti thought it was so creepy, and potentially inappropriate given Dylan's motorcycle accident a decade earlier, that they scrapped it.

Bowie was hardly lucid in 1976, but you bet he knew exactly what he was doing with that verse. The mysterious injuries from Dylan's 1966 accident gave him the excuse to disappear from the rat race for years, whereas the full complement of wounds Bowie sustained in L.A. were proudly displayed for a while: the Station to Station-era diet of cocaine, red peppers, and milk, and the ensuing physical and psychic degradation that led him to endorse fascism, fear the occult, and allegedly keep his urine in the fridge lest anyone steal it. (From a flushed toilet?) When he realized he had to leave Hollywood and kick his prodigious habit, West Berlin appealed for its anonymity, though unlike Dylan, Bowie would make his own recovery a matter of public record. Both artists were escaping paradigmatic American success by retreating into themselves. Where Dylan let rumors of death fester, Bowie opened his hermitage to the world, reinforcing his outsider myth.

The Bowie of this era is a tragic figure: strung out and prone to spending days awake watching the same films on a loop. He was broke from the aftermath of a bad managerial deal and drained by the related ongoing court case, and so paranoid that, after his destitute charge Iggy Pop pushed him in the pool at the residential Château d'Hérouville studio in France, he had it exorcized to avoid being touched by the dark stains that he believed lurked at the bottom.

Yet Bowie's sense of purpose was at least somewhat intact. He applied exacting pressure on Iggy to make The Idiot as good as he knew it could be, and brought similar determination to Low, albeit the kind where having very few aims was its own liberating objective. Whatever they made didn't even have to be released, he told his new collaborator Brian Eno, who was brought in alongside Station to Station's crack band to further develop that album's hybrid of electronic R&B."

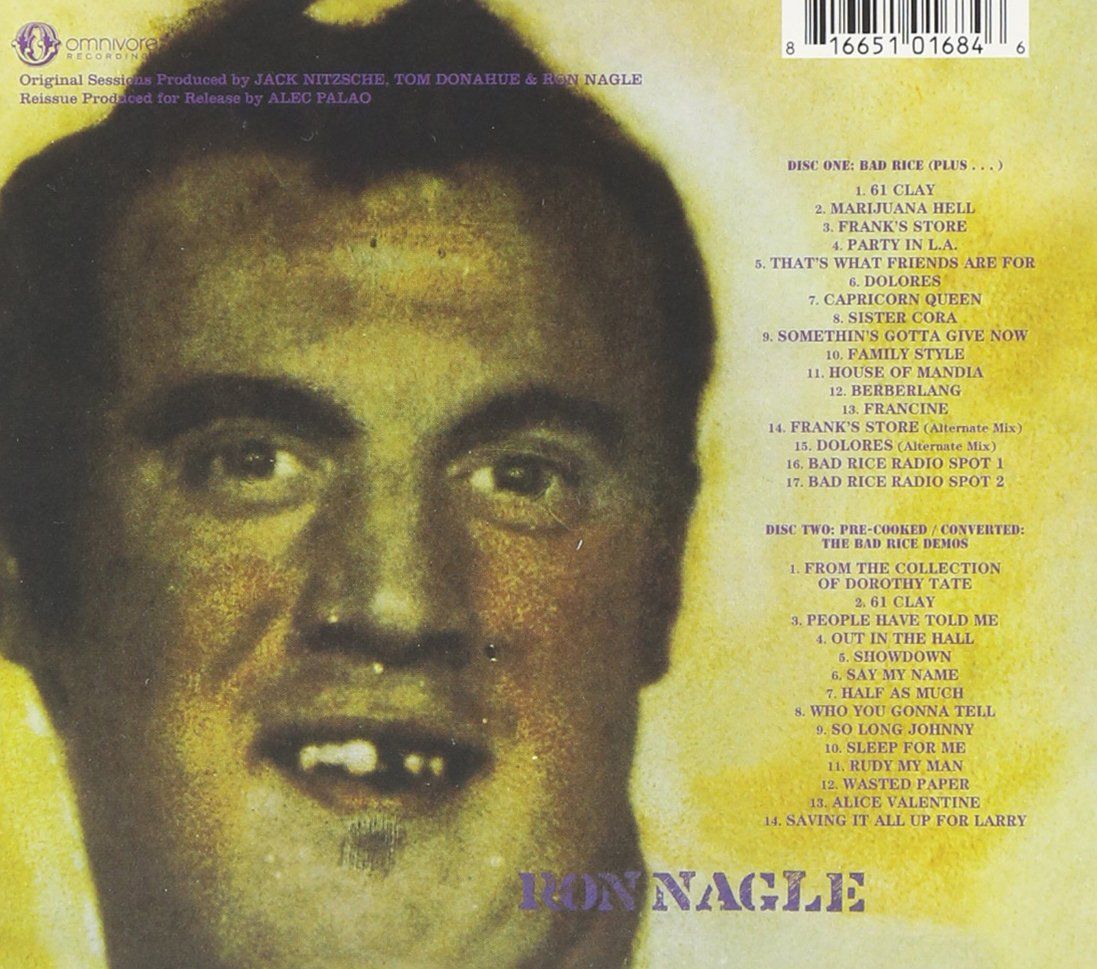

Ron Nagle - Bad Rice

Back in the early 1970's, while attending college in Dayton, Ohio, I used to go to this great record store called The Forest which was just a hop-skip & a jump off-campus. After ditching a class, I'd head down to The Forest and spent many happy hours thumbing thru the album racks in the used record section. These albums were promotional castoffs that local disc jockeys used to sell to the store owner for cash. Besides the low prices for these vinyl wonders (as I recall, $2.00 was the going rate), I often would buy albums just because I liked the cover…or the title of the record…or the names of the songs…or just had a good feeling about the record in general. Such was the case when I picked up a copy of Bad Rice by Ron Nagle back in 1970.

One thing that immediately caught my eye was the fact that the Bad Rice album was on the Warner Bros. record label which just so happened to be my favorite record label during the late 60's and early to mid-seventies. I really like the fact that the Warner Bros label seemed to always have the most eclectic artists on their roster; folks like Arlo Guthrie, the Grateful Dead, Van Dyke Parks, John Simon, The Youngbloods, Van Morrison, Little Feat and more. It was obvious that the label placed a high premium on good songwriters and at first listen, that's what Ron Nagle sounded like; a good songwriter along the lines of, say, Randy Newman. His voice was not a distinctive one but the songs he wrote were tiny snapshots of life that have lingered in my memory over the years.

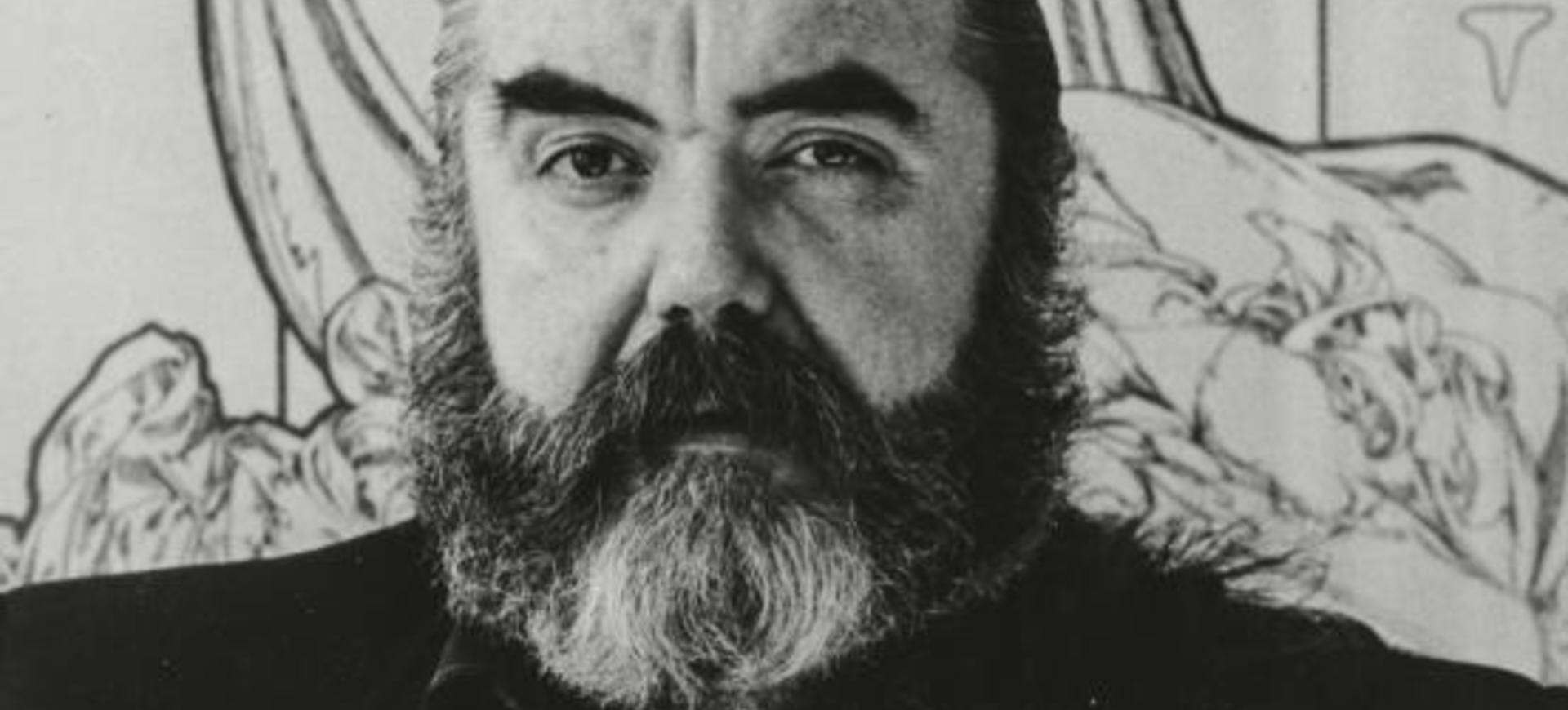

Jack Nitzsche in the studio

A 2016 Mojo Magazine article describes Nagle working with Nitzsche: "Ensconced in Wally Heider Studios, Nitzsche listened to Nagle’s demos: ‘Jack heard Delores and Frank’s Store and went I’ll Do It. I just about fell on the floor. He wasn’t as interested in Capricorn Queen and 61 Clay so he pulled Ry Cooder in on those.”

Performance film

In the article, Nagle indicates that at the time of the Bad Rice sessions, Nitzsche was also working with Ry Cooder on the soundtrack to the film, Performance.

Nagle goes on to describe the chaotic atmosphere of the Bad Rice sessions, "We'd get fucked up constantly. We got kicked out of our own sessions by engineer Bruce Botnick and Bruce worked with Jim Morrison. After about 10 Heinekens, Jack'd go through a demonic transformation. He had this kendo stick and would start speaking like an American Indian, saying 'You betray me now' in this kinda pigeon English. Oh fuck, it was scary. He did that to (Barbara) Streisand. He didn't care."

Ron Nagel - Marijuana Hell (single)

For me, the song on this album that immediately caught my attention was a ditty called Marijuana Hell in which the song's narrator laments a young girl's devotion to smoking that wacky weed. I initially took this song to be a satirical rock & roll version of the movie, Reefer Madness, but after repeated listens it seemed to me that Nagle's voice was a bit too sincere to make that stick. Many folks felt this anti-drug tune didn't fit the underground rock ethos of the times but I remember thinking that it was pretty dang courageous for somebody to take this stance back then. Years later, I was actually inspired by this very tune to write an anti-drug song called Cocaine & Promises for a band I was in called the Freelance Vandals. Thanks for the inspiration Ron!

Ultimately, the Bad Rice album did not sell in any large numbers and soon appeared in the cut-out bins in many record stores. In the Mojo article, Nagle reflected on the album's failure in the marketplace, "I had a hangover for 15 years and I beat myself up a lot more than I had to. It took me a long time to realize what I had there but I'm still writing and I still make art and I'm doing Ok."

Years later, in an SF Gate article, Nagle reflected on the songs he had written for Bad Rice, “My songs were melancholy, darker stuff that was not particularly popular at the time…It wasn’t cool in the happiness bastard era of the ’60s. I wrote what I knew, and if I didn’t know it, I would just write the story. I didn’t want to save the world or make everyone brothers.”

In January 2015, Bad Rice was reissued in an expanded 2 disc version by the boutique label, Omnivore Recordings. Disc 2 of the set is Pre-Cooked / Converted: The Bad Rice Demos which features pre-production demos which Nagle recorded for this cult album.

Here's an excerpt from the kqed.org site:

"To be fair, Bad Rice was a tough sell at the time. It’s an odd mix of styles — Stones-y rockers and quasi-Tin Pan Alley ballads — around Nagle’s melancholy, character-driven tales. Not the kind of stuff you’d hear on AM pop radio of the day, or even the insurgent, freer FM side. Not to mention that the cover featuring Nagle artwork depicting a pile of, uh, rice wasn’t exactly a sexy draw for impulse buyers, and the artist didn’t tour to support the album. Not surprisingly, it sunk with nary a trace, save for a handful of glowing reviews (one by Rolling Stone’s Ed Ward) and an even smaller clutch of devoted fans (eventual producer-to-the-stars T-Bone Burnett among them). It wasn’t so much ahead of its time. It never really had at time.

DJ Tom Donahue, the godfather of free-form FM radio, took him under his wing and got him connected to producer Jack Nitzsche (the Phil Spector protégé, then fresh from his work on Neil Young’s solo debut, and the remarkable soundtrack for the Mick Jagger-starring movie Performance) and then Warner Bros. (Donahue also produced three songs that wound up on Bad Rice).

But perhaps it just took 45 years to throw some perspective on this album. Heck, it took Nagle a while to get perspective on it himself. 'It’s weird', he says. 'I went through ups and downs over the years where I personally hated it and then loved it. It’s taken a long time to understand what I was doing myself. No. 1, I was in a pretty oblivious state, drinking and drugs. I’ve been sober more than 30 years now, but most of these songs were created in an altered state. I listen to it now and, yeah, some of this writing is pretty interesting. I don’t mean that egotistically. But something was going on I wasn’t aware of when I was writing this. I don’t know if it was ahead of its time, but it was out of step.'

It should be noted that Nagle pulls no punches with his disdain for the hippie music and culture of his hometown in the time leading up to the making of the album. When he went to the acid-fueled shows at the Fillmore, with their endless solos and such, he sniffed derisively. 'I wasn’t raised at that time. I was from the ‘50s — black music, doo-wop, soul, later R&B and then Motown,” he says. “I couldn’t identify with San Francisco music at all, or art. I was born and raised here, but couldn’t dig it. Beatnik era, yeah. I was in North Beach. I saw all the great jazz acts. I saw Lenny Bruce in person. I was out of step.'

Besides the quirky songs that featured a variety of musical styles (country-rock, FM pop, folk, blues), the picture adorned the rear cover of album, seemed to have an unsettling effect on those who gazed upon it which ultimately drew people to the music.

In closing, here's a review of the Bad Rice album from theseconddisc.com site:

"Rare is the cult album that actually lives up to its mystique. But rare is Ron Nagle's Bad Rice. This artifact from the Mystery Trend leader and acclaimed ceramic sculptor, originally released on Warner Bros. Records circa 1970, has recently been given new life by Omnivore Recordings in a deluxe 2-CD edition that's an early candidate for Reissue of the Year. One part David Ackles, one part Randy Newman and the rest pure Nagle, Bad Rice likely wasn't helped all those decades ago by its inscrutable title and unattractive cover artwork. Potential buyers would have had no clue that the album's sleeve housed a truly varied collection of eleven striking character studies in pop and rock, balancing so-called confessional songwriting (that earned the artist James Taylor and even Elton John comparisons) with boisterous, Stones-worthy rock songs. For a debut album, it might have been too diverse in its stylistic forays, but listening today, its air of surprise is among its strongest suits. Nagle was joined on Bad Rice by illustrious producer Jack Nitzsche who oversaw a cadre of top musicians including Ry Cooder, Sal Valentino of The Beau Brummels, John Blakeley, Brad Sexton, Steve Davis, Mickey Waller and George Rains.

Ry Cooder's searing guitar anchors the matricidal opener 61 Clay, a raunchy rocker that establishes Nagle as a chronicler of the unexpected. It shouldn't be surprising that Nagle's art is inextricably tied to his music - not just in his use of the word clay in the first song's title (it came from the gallery address at which Nagle had a show) but the fact that the tune is about the character of Chuckie, whose unappealing visage Nagle leafleted around San Francisco to drum up attendance for the show. (You can get a glimpse of gap-toothed Chuckie on the back cover of the album.) But bad boy Chuckie is just one of the characters introduced by Nagle on Bad Rice. A church-style organ opens Sister Cora, a quirky piece about a faith-healin' mama ('And she did it all/Just by stirrin' the leaves in her tea!'). Then there's the lady named Dolores, subject of a wrenchingly melancholy memory play adorned with Nitzsche's lavish orchestration.

The richly melodic Dolores is one of the two indisputable high points on Bad Rice. Nitzsche's graceful strings and orchestral accompaniment add greatly to the second, as well - the beautiful, somber and moving Frank's Store. The germ of Frank's Store, Nagle explains in Gene Sculatti's excellent liner notes, was in Nagle's own experience. He drew upon his memories of the local corner groceries of his childhood for its four heartbreaking minutes. Party in L.A., in which the personal and the political conflate, was also based in autobiography - specifically, an incident with Nagle's first wife as filtered through his never-quite-straightforward lyrical style. The brash Capricorn Queen (featuring fine slide guitar work), on the other hand, was apparently written as an ode to his second wife, who's kept him on the straight and narrow for decades.

Musically, Bad Rice is as diverse as its characters. One voice-and-piano ballad puts Nagle in the company of Burt Bacharach and Carole Bayer Sager, Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman, and Paul Williams...Nagle's variation on the theme is an elegant, melodic, and tender admission of the roles played in a relationship, showing another side of the edgy songwriter. Somethin's Gotta Give Now by Nagle and Frank Robertson is loose, steel guitar-flecked country-rock, while barroom piano and ragtag sing-along background vocals enliven the freewheeling, offbeat Family Style with its flavor of The Band (and makes it clear why some writers hung the Americana tag on Bad Rice.)

The goofily over-the-top, and infectiously catchy, reefer madness rock-and-roll riff Marijuana Hell ('All it took was just one try/Ever since he's been too high!') was co-written by John Blakely and also features Cooder's stinging guitar. It would have, in lesser hands, crossed the line into novelty. For its closing salvo, Bad Rice appropriately offers the schizophrenic, widescreen House of Mandia, which juxtaposes a hard-rocking verse with an orchestrated, tropical chorus to tell the story of an average Joe's fantasy-island dreams. Over its eleven tracks, Bad Rice touches on all points on the spectrum of American music, pointing the way towards Nagle's future songs that he would write for talents as disparate as Barbra Streisand and The Tubes. The album had everything, it seemed...except a hit single."

Joe Walsh - Barnstorm

Ah, the Joe Walsh album, Barnstorm, is one of the gems in my record collection to be sure. It belongs to an era of rock music when artists were not only allowed to experiment outside of the styles in the popular record charts, they were encouraged to do it! Records like Barnstorm and, say, Sgt. Pepper by The Beatles exist in realm where imagination is king.

After leaving the James Gang in 1971, Joe Walsh gathered together Kenny Passarelli (bass) and Joe Vitale (drums/multi-instruments) to form a new entity which he called Barnstorm. Thus, this album is actually a self-titled group album and not really a true Joe Walsh solo album per se.

Joe Walsh - Barnstorm (full album)

Bill Szymczyk (Barnstorm Producer)

The Barnstorm album, produced by Bill Szymczyk, who had worked with Walsh on several James Gang albums, sports a multi-layered, open bucolic sound. It's almost as if you're strolling across a great lawn that stretches out before you. Each song is enhanced with textures of acoustic guitars and synthesizer; all done in tasteful balance in a manner that supports the songwriting more than the performer; an act that is frequently lost in today's modern record production.

From the Colorado Music Experience site: “Walsh moved to Colorado to work with Szymczyk, who had heard rumors about Caribou Ranch, but the studio was unfinished. Szymczyk pleaded with owner James William Guercio to record at Caribou Ranch, which was still unfinished. The location would inspire one of Walsh’s biggest hits, “Rocky Mountain Way,” and Caribou would be the center of Szymczyk’s operations for the rest of the decade. Meanwhile, Szymczyk used Walsh, Joe Vitale and Kenny Passarelli as the studio house band.”

Pete Townshend's Arp Synthesizer

In some rock journals, it's been noted that Walsh's primary musical influence during this album was the work being done by Pete Townshend (of the Who) with the ARP Synthesizer (pictured above). A closer look at Townshend's work on the Who's 1971 masterwork Who's Next reveals the elements that probably entranced Walsh to go on to create the Barnstorm record in the first place --- elegant sounds of layered acoustic guitars and ARP synthesizer riffs that were paired off against harder rock sounds of bass, drums & electric guitar.

When Barnstorm was released in 1972, the record received a mediocre response from the rock & roll crowd. It's been noted that of all of the songs on this record, only the hard rock styled Turn To Stone has (ironically) emerged as a popular favorite in the Joe Walsh songbook over the years. Ah, further proof that many of the truly great records are always ahead of their time, eh?

Here's an excerpt from a 2013 article in The Paris Review called The Tao of Joe Walsh by Matt Domino:

"Barnstorm was recorded in 1972 after Walsh left the James Gang (his first group with whom he made the legendary riff-rock track Funk 49) and moved to Colorado to regroup...Even though Barnstorm has no true hits, it is not a particularly difficult or extremely subtle album—the kind that needs time and repeated listens. Instead, there is something fundamental in its music, in the way that the album flows—at times, songs are linked by the sound of blowing wind—that makes you say, 'Yes, this is a rock ’n‘ roll album as an ideal; something sturdy and lasting that Plato would have approved of. There really was once an art to this.'

Joe Walsh deserves to be placed in the same category as Jimmy Page and Led Zeppelin when it comes to the contribution of the album as art form...The opening track is called Here We Go, which, as a title for a first song, speaks for itself. The first sounds on record are ominous acoustic guitar strums, with subtle touches of electric guitar. Then, the aforementioned perfectly recorded drums rumble and thunder into the mix—but only for a brief moment. The song quiets down again for a few bars, before taking off with Walsh, in his trademark light-molasses whine, singing the titular line of the track while the electric guitar crunches, the acoustic guitar hums, and an organ line lifted straight from the Beatles’ Let it Be–era propels the song and gives it a glowing, late-summer radiance. Once the theatrics end, the track turns into an extended guitar and synthesizer jam—with searing solos that hit you from every angle—that slowly becomes a haunting piano meditation complete with mountain-wind sound effects. And that’s just the first song!

Here We Go segues seamlessly into Midnight Visitor, which is replete with high-register, twanging Walsh vocals covered in echo and backed by lonesome trail acoustic guitar before turning into an organ-based, wordless chorus that sounds like a carnival on the last weekend in August—the kind you bring a denim jacket to, just in case.

Through the course of Barnstorm, you get a chance to revel in the thick, devil’s food cake funk, of Mother Says, with its suddenly popping bass lines and incredibly chunky guitar and organ and intervals of absolutely soaring—there is no other word—piano- and guitar-based instrumental breaks.

Then, there are the melodic dynamics of Birdcall Morning, full of textbook slide guitar playing and staggering drum sounds. The fluid and near-pastoral nature of the song bring to mind the overwhelming sensation of the last beach day of the year, when the waves are choppy and strong, but the water is warm and the beer back on the shore is cool and ringed with sand.

And later, there is the McCartney/Brian Wilson on steroids ballad, I’ll Tell the World with plenty of the playful and stacked backing vocals that you would want from one of those two pop masters.

This all leads to the album’s denouement—the back-to-back of Turn to Stone and Comin’ Down. The former is an epic guitar rocker that rides on the back of a furious, hair-of-the-dog lead guitar line and supportive but still aggressive slide playing. The entire song is menacing, slightly desperate with the residue of the night before and full of dark guitar fireworks. But it lacks the smiling, winking buzz of Walsh’s later hits, which makes it no surprise that it only reached number ninety-three as a single. Meanwhile, Comin’ Down is a perfect album ender just as Here We Go is a perfect album opener. It is a barely-two-minute acoustic meditation with vaguely poignant lyrics such as, Comin’ down, comin’ round to see you / To see if maybe you know who I am. The song, and entire album, ends on a fading harmonica and lightly picked acoustic guitar."

Sparks - Kimono My House

In my final year at The University of Dayton, I became friends with a fella named Billy "The Mountain" Cairns who quickly became the drummer in a trio I put together that was called the Freelance Vandals. Aside from doing gigs with Billy, he also was a major influence in checking out the latest sounds on the rock & roll scene. Along with the Ramones and Queen, Billy turned me on to a quirky combo called Sparks!

The first lineup of the Freelance Vandals circa 1974

Paul Polanki (saxophone),

Billy "The Mountain" Cairns (drums)

& Johnny Pierre (Vocals, Guitar)

Sparks - Kimono My House (full album)

From the trunkworthy.com site:

"Here’s how pivotal 1974’s Kimono My House is: Prior to it, no other single song collection had combined the baroque wit and grandeur of Gilbert and Sullivan with the brash ’60s power of The Who and The Kinks, the proto-punk of The New York Dolls and the Stooges, the ingenious art glitter of Roxy Music and T. Rex, the virtuoso derring-do of Frank Zappa, the propulsive stomp of Slade, and the bubblegum dynamics of Sweet—not to mention what Sparks themselves had already brought to the drawing board.

The Los Angeles-based duo consists of the Brothers Mael: Ronald, the manic, Chaplin-mustachioed elder, who composes the songs and doesn’t so much play the keyboards as he does possess them, and Russell, the younger, of whom the term frontman seems insufficient and swashbuckler comes closer.

Freak-pop provocateur Todd Rundgren discovered Sparks and produced their first two LPs, fitfully potent confections that invite comparisons to any number of rambunctious rock ’n’ roll rule-breakers of the day, although Old Grey Whistle Test TV host Bob Harris may have best nailed it by likening Sparks to The Mothers of Invention meet The Monkees.

Kimono My House, though, is the album where Sparks put all the aforementioned influences together and, bolstered by their own combustive genius, charged forward—and, even now, have just kept going. Here is the very record where Sparks became Sparks.

Consider Kimono’s opening track. This Town Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us. Swooping in on dreamlike electric piano, Russell Mael talks tough by singing of jealousy and zoo animals in a falsetto that Tiny Tim would require a tank of helium to reach.

From there, Russell’s declaration of the title is followed by an actual gunshot ricochet, Gestapo boot beats, and fuzzy guitars set to raze any ear they can reach. In those first 30 seconds alone, Sparks simultaneously dismantles, one-ups, and supersedes the hyper-machismo of big, loud, bad boy rock circa ’74.

The onslaught only intensifies as the song storms onward, commingling Old West tropes, battlefield percussion, bop-along bubblegum dynamics, and airy-fairy dandyism, all as the angelic-voiced fop hero smashes home to his rival that the girl is his, their local confines are too tight, and that 'it ain’t me who’s gonna leave!'

With This Town Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us, Sparks lays forth the bridge connecting glitter to punk. Each successive song on Kimono My House serves as another plank moving forward, although not just to, say, The Sex Pistols (whose Never Mind the Bollocks was once proclaimed as rock’s greatest record by the Maels) but to an endless future where Ron and Russell continue to inspire.

Here in Heaven cheekily reveals the details of a lovers’ leap suicide pact gone wrong, sung from a boringly antiseptic afterlife by the deceased Romeo, as he was the only one to actually jump."

From the loudersound.com site:

"Half a century on from their debut album, Sparks continue to baffle and bewilder like no force in musical history, but it was 1974's Kimono My House that carried This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us into the nation’s living rooms, radios and hearts.

With an image contrived from purest eccentricity, Sparks were a musical anomaly but also ideal constituents for the glam rock collective. LA brothers Russell and Ron Mael fashioned a bubbly and camp musical style not entirely dissimilar to that of Roxy Music, but it was Sparks’ unconventional image that truly captured the national imagination.

In an interview with The Guardian, Ron Mael stated that 'The vocals on This Town Ain't Big Enough For The Both of Us sound so stylized because I wrote it without any regard for vocals and Russell had to adapt. We were shocked when the record company thought it was a single, but doing Top Of The Pops had a tremendous effect. Suddenly there were screaming girls. We recorded it during the energy crisis and we were told that because of the vinyl shortage it might never come out.'

While vocalist Russell vamped for his life with cherubic curls and a daunting falsetto, elder brother Ron played a quizzical Hitler on keyboards. This Town... and Amateur Hour became glam staples and, incredibly, they’re still at it. Still releasing albums. Still as strange and as adventurous as they ever were."

Thank you Billy for turning me onto some of those fantastic albums back in the 70's!